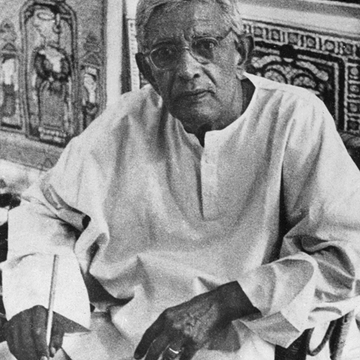

How Jamini Roy Revolutionised the Modern Indian Art scene

Say “modern” art and many people think of abstract shapes and forms. But there is much, much more to modern Indian art, and nowhere is this more obvious than in the extremely popular works of Jamini Roy, the painter who brought Indian folk art onto the mainstream canvas. At a time when many of his contemporaries were turning to western forms for impression, Roy, who had trained in western art, returned to the great folk art traditions of India. And he, and Indian art itself, have never looked back since.

Jamini Roy was born in Beliatore village in the Bankura district of West Bengal on April 11, 1887. His father Ramaratan Roy was a government officer and an amateur artist himself. His father’s encouragement and the rural settings of Roy’s childhood played a huge role in shaping his future artistic sensibility. Roy grew up surrounded by artisans making pots, dolls, idols, and textiles. Thus, he imbibed the language of rural Indian arts. Since Roy showed a prolific talent for art at an early age, he enrolled at age 16 in the Government School of Art, Calcutta. At the Government School in British India, the academic training was rigorous and focussed on the techniques of classical western Art as well as the then-newer painting forms of impressionism and post-impressionism. Thus, Roy acquired the technical skills necessary to paint in formal western traditions. From the very beginning of his career, Roy was interested in colour, bold, broad lines, and stylized folksy canvasses. He also deeply admired European artists like Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gaugin. Van Gogh is known for his thick brush strokes and impressionistic landscapes, while Gaugin is famous for his return to folk and so-called primitive art forms. Roy was also influenced by the painter Abanindranath Tagore and the nationalist Bengal school of art, which focussed on depicting Indian subjects. Fusing these two influences, his early artworks were landscapes and oil paintings depicting Santhal tribespeople and everyday life in rural Bengal. Despite the technical prowess of the first half of his career, Roy continued to be restless, as if he still had not found his artistic language. When great artists do not find a language, they create a new one. Or reinvent an old form to express their vision. And that is what Roy did as he transitioned to the peak of his artistic career.

Back to his roots

Although Roy’s subjects had always been Indian, by the 1920s his search for a uniquely Indian technique to depict them had become more urgent. His art itself showed him the direction in which to head for answers. Increasingly, his landscapes had been getting flatter and more two-dimensional, the quest for photorealism forgotten. Now, Roy began to look to the world of Indian folk art and craft for a new vocabulary. He began visiting his village home in Beliatore more often, picking up nativist and folk influences of the rural artists of his childhood. He was also intrigued by the pat or cloth paintings that local artists sold outside Kalighat in Calcutta. An indigenous style that developed in the 19th century, Kalighat art featured boldly sketched figures against plain backdrops. Along with Kalighat paintings, Roy also began taking a renewed interest in eastern India’s patachitra style scroll painting and the terracotta temple sculptures of nearby Vishnupur began to dominate his vision. From these art forms, he evolved a new style that was highly linear, colourful, and ornamental. The figures are the centre stage of his canvas, grave and challenging in expression, and contained in thick, dynamic strokes. Often the canvasses are bordered with patterns and motifs, as in the traditional Indian style. It was not just his style, Roy’s medium changed too. He gave up painting in oil-based pigments, choosing instead to grind and mix his own earth colours and crushed rock pigments. In 1929, Roy held a solo exhibition at his alma mater, the Government Art School of Calcutta, showcasing his new paintings. The master of a new folk-based Indian art had arrived. Inaugurating Roy’s exhibition, Sir Alfred Watson, then editor of The Statesman, famously said:

“Those who study the various pictures will be able to trace the development of the mind of an artist constantly seeking his own mode of expression. His earlier work done under purely Western influence and consisting largely of small copies of larger works must be regarded as the exercises of one learning to use the tools of his craft competently and never quite at ease with his models. From this phase we see him gradually breaking away to a style of his own.”

Celebrating the women of India

Roy’s subjects in his mature phase are sometimes figures from Indian mythology and religions, such as Durga and Ganesh, Radha-Krishna, or Mary with Jesus. Sometimes they are everyday people and even animals, such as in his famous paintings like Three Pujarins and Cat and Lobster. His figures are flat, unmissable, and bold, the colours vibrant and vivid. The images of women dominate his paintings, whether it be Radha, Yashoda, priestesses, Santhal women, brides, or housewives. Thus, he celebrates the Indian feminine. Roy’s woman with her large stylized eyes and bold features is a symbol of beauty and power, one that adorns Indian households not just in West Bengal, but all over the country. Contrary to what many people think, Roy’s influences were not just European and Indian, he was also heavily inspired by the minimalism of Japanese art and the murals of Byzantine church paintings. His diverse representation of figures from Hindu to Christian religions shows Roy’s deeply syncretic idea of Indian culture. As calls for independence became stronger during the 1930s and 1940s, Roy’s folk-based diverse style also proclaimed a new Indian identity: one which was proud of its roots and multicultural.

An artist for the people

Roy continued to evolve his visual vocabulary throughout his life. Along with his colourful flat paintings, he also developed a more minimalistic, monochromatic style, such as in the calligraphic sketch Bal Gopal. Here, the colours are muted and the ornamentation of his panel paintings gives way to the lines of the central image. Roy also continued to create realistic portraits along with his unique folk-style paintings throughout his career, whether it was his portrait of Rabindranath Tagore in 1910 or that of Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi in the mid-1940s. Even his subjects evolved: during the 1940s, Roy increasingly painted Jesus Christ, but in a style that was wholly Indian and rustic. Thus, he challenged the traditional Western iconography of Christ. However, despite his growing fame and influence, Roy never sold a painting over Rs 350 in his lifetime. He was also in the habit of giving away his works freely or letting his works be copied. This reflected Roy’s philosophy that art should be non-elitist and was meant to be created and consumed by the masses. Roy’s democratic vision of art is central to understanding his evolution as a painter. It is this that took him from academic art to folk styles. He wanted his art to be accessible, and shunned the idea of the artist as a genius in an ivory tower, In fact, rather than a painter, Roy preferred to be called a patua, the name for a folk scroll artist. Roy continued to paint into his sixties and seventies but withdrew from public life as he aged. He passed away in his beloved Calcutta in 1968, survived by four sons and a daughter. Roy was awarded the Padma Bhushan by the Indian government in 1955 and elected Fellow of the Lalit Kala Akademi in 1956. On 24th April 1972, Roy’s works were granted the status of “national treasures” by the Government of India. He is one of only nine Indian artists whose works have been awarded a similar honour.

Jamini Roy’s legacy

Roy remains one of the most popular artists of modern India, his artworks and their prints occupying a huge space in the public imagination. His works are now known by their themes, such as his Mother and Child series, or his Jesus series from the 1940s. What makes Roy’s work so enduring is its surprising modernness: the graphic lines, the purity of depiction, and his unique vision. Further, he was one of the first Indian modernists to invent a visual language that was wholly new, yet completely rooted in Indian culture. That’s why Roy remains distinctive and current, with his paintings continuing to be highly valued (in 2021, a Jamini Roy work fetched US dollars 583,784 or INR 4.5 crore). Roy’s works are housed all over the world, from the collections of the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi and Victoria and Albert Museum in London, among others.